![Solithromycin.svg]()

![ChemSpider 2D Image | Solithromycin | C43H65FN6O10]()

Solithromycin

- Molecular Formula C43H65FN6O10

- Average mass 845.009 Da

CEM-101;OP-1068

UNII:9U1ETH79CK

(3aS,4R,7S,9R,10R,11R,13R,15R,15aR)-1-{4-[4-(3-Aminophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]butyl}-4-ethyl-7-fluoro-11-methoxy-3a,7,9,11,13,15-hexamethyl-2,6,8,14-tetraoxotetradecahydro-2H-oxacyclotetradecino[4 ;,3-d][1,3]oxazol-10-yl 3,4,6-trideoxy-3-(dimethylamino)-β-D-xylo-hexopyranoside

2H-Oxacyclotetradecino[4,3-d]oxazole-2,6,8,14(1H,7H,9H)-tetrone, 1-[4-[4-(3-aminophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]butyl]-4-ethyl-7-fluorooctahydro-11-methoxy-3a,7,9,11,13,15-hexamethyl-10-[[3,4,6-trideox ;y-3-(dimethylamino)-β-D-xylo-hexopyranosyl]oxy]-, (3aS,4R,7S,9R,10R,11R,13R,15R,15aR)-

3,4,6-Tridésoxy-3-(diméthylamino)-β-D-xylo-hexopyranoside de (3aS,4R,7S,9R,10R,11R,13R,15R,15aR)-1-{4-[4-(3-aminophényl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl]butyl}-4-éthyl-7-fluoro-11-méthoxy-3a,7,9,11,13,15-hex améthyl-2,6,8,14-tétraoxotétradécahydro-2H-oxacyclotétradécino[4,3-d][1,3]oxazol-10-yle

Solithromycin (trade name Solithera) is a ketolide antibiotic undergoing clinical development for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)[1] and other infections.[2]

Solithromycin exhibits excellent in vitro activity against a broad spectrum of Gram-positive respiratory tract pathogens,[3][4] including macrolide-resistant strains.[5] Solithromycin has activity against most common respiratory Gram-(+) and fastidious Gram-(-) pathogens,[6][7] and is being evaluated for its utility in treating gonorrhea.

- May 2011: Solithromycin is in a Phase 2 clinical trial for serious community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and in a Phase 1 clinical trial with an intravenous formulation.[8]

- September 2011 : Solithromycin demonstrated comparable efficacy to levofloxacin with reduced adverse events in Phase 2 trial in people with community-acquired pneumonia[9]

- January 2015: In a Phase 3 clinical trial for community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP), Solithromycin administered orally demonstrated statistical non-inferiority to the fluoroquinolone, Moxifloxacin.[10]

- July 2015: Patient enrollment for the second Phase 3 clinical trial (Solitaire IV) for community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) was completed with results expected in Q4 2015.[11]

- Oct 2015: IV to oral solithromycin demonstrated statistical non-inferiority to IV to oral moxifloxacin in adults with CABP.[12]

- July 2016: Cempra Announces FDA Acceptance of IV and oral formulations of Solithera (solithromycin) New Drug Applications for in the Treatment of Community-Acquired Bacterial Pneumonia.[13]

![Image result for Solithromycin]()

![Image result for Solithromycin]()

Structure

X-ray crystallography studies have shown solithromycin, the first fluoroketolide in clinical development, has a third region of interactions with the bacterial ribosome,[14] as compared with two binding sites for other ketolides.

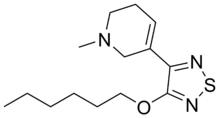

The only (previously) marketed ketolide, telithromycin, suffers from rare but serious side effects. Recent studies[15] have shown this to be likely due to the presence of the pyridine–imidazole group of the telithromycin side chain acting as an antagonist towards various nicotinic acetylcholine receptors.

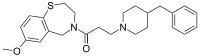

Macrolide antibiotics, such like erythromycin, azithromycin, and clarithromycin, have proven to be safe and effective for use in treating human infectious diseases such as community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP), urethritis, and other infections.

Because of the importance of macrolide antibiotics, there has been growing recent interest in this area as exemplified by the new fourth-generation macrolide solithromycin , which is developed by Cempra Pharmaceuticals as the first fluoroketolide antibiotic that has recently completed phase III clinical trials and demonstrates potent activity against the pathogens associated with CABP, including macrolide- and penicillin-resistant isolates of S. pneumoniaeis

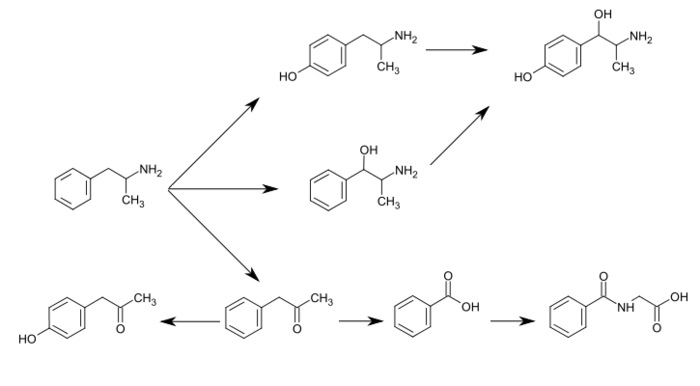

To date, all macrolide antibiotics are produced by chemical modification (semisynthesis) of erythromycin, a natural product produced on the ton scale by fermentation. Depicted are erythromycin and the approved semisynthetic macrolide antibiotics clarithromycin, azithromycin and telithromycin along with the dates of their FDA approval and the number of steps for their synthesis from erythromycin. The previous ketolide clinical candidate cethromycin and the current clinical candidate solithromycin are also depicted. It is evident that increasingly lengthy sequences are being employed in macrolide discovery efforts.

![Chemical differentiation of solithromycin from telithromycin]()

ref…… http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0968089616306423

RETROSYNTHESIS

![Figure]()

SYNTHESIS

Scheme . Reported Route for the Synthesis of Solithromycin, Fernandes, P. B.; Chapel, H. ; Patent WO 2010/048599, 2009

PATENT

WO 2016210239,

![]()

![]()

Clip

Figure 4: A convergent, fully synthetic route to solithromycin.

FromA platform for the discovery of new macrolide antibiotics

- Nature, 533, 338–345 (19 May 2016), doi:10.1038/nature17967

![]()

![]()

residue was purified by column chromatography over silica gel (10% methanol–dichloromethane + 1% 30% aqueous ammonium hydroxide) to afford amine 49 as a pale yellow oil (1.11 g, 96%). TLC (10% methanol–dichloromethane + 1% 30% aqueous ammonium hydroxide): Rƒ = 0.12 (UV, anisaldehyde).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 8.26 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H), 7.23 – 7.10 (m, 3H), 6.72 (ddd, J = 7.8, 2.3, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 4.47 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.70 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.05 – 1.95 (m, 2H), 1.57 – 1.47 (m, 2H).

13C NMR (126 MHz, CD3OD) δ 149.51, 149.15, 132.32, 130.72, 121.99, 116.32, 113.14, 51.20, 41.86, 30.64, 28.66.

FTIR (neat), cm-1 : 2424, 1612, 1587, 783, 694.

HRMS (ESI): Calculated for (C12H17N5 + H)+ : 232.1557; found: 232.1559.

SPECTRAL DATA OF SOLITHROMYCIN

![]()

![]()

![]()

The residue was purified by column chromatography (3% methanol–dichloromethane + 0.3% 30% aqueous ammonium hydroxide) to provide solithromycin (170 mg, 87%) as a white powder.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ: 7.82 (s, 1H), 7.31 – 7.29 (m, 1H), 7.23 – 7.15 (m, 2H), 6.66 (dt, J = 7.2, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.89 (dd, J = 10.3, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (td, J = 7.1, 1.5 Hz, 2H), 4.32 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 4.08 (d, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.82 – 3.73 (m, 1H), 3.68 – 3.60 (m, 1H), 3.60 – 3.49 (m, 2H), 3.45 (s, 1H), 3.20 (dd, J = 10.2, 7.3 Hz, 1H), 3.13 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 2.69 – 2.59 (m, 1H), 2.57 (s, 3H), 2.51 – 2.42 (m, 1H), 2.29 (s, 6H), 2.05 – 1.93 (m, 3H), 1.90 (dd, J = 14.5, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 1.79 (d, J = 21.4 Hz, 3H), 1.75 – 1.60 (m, 4H), 1.55 (d, J = 13.0 Hz, 1H), 1.52 (s, 3H), 1.36 (s, 3H), 1.32 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 1.28 – 1.24 (m, 1H), 1.26 (d, J = 6.1 Hz, 3H), 1.20 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 1.02 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), 0.89 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 216.52, 202.79 (d, J = 28.0 Hz), 166.44 (d, J = 22.9 Hz), 157.19, 147.82, 146.82, 131.72, 129.63, 119.66, 116.14, 114.71, 112.36, 104.24, 97.78 (d, J = 206.2 Hz), 82.11, 80.72, 78.59, 78.54, 70.35, 69.64, 65.82, 61.05, 49.72, 49.22, 44.58, 42.77, 40.86, 40.22, 39.57, 39.20, 28.13, 27.59, 25.20 (d, J = 22.4 Hz). 24.28, 22.14, 21.15, 19.76, 17.90, 15.04, 14.70, 13.76, 10.47.

19F NMR (471 MHz, CDCl3) δ –163.24 (q, J = 11.2 Hz).

FTIR (neat), cm–1 : 3362 (br), 2976 (m), 1753 (s), 1460 (s), 1263 (s), 1078 (s), 1051 (s), 991 (s).

HRMS (ESI): Calcd for (C43H65FN6O10 + H)+ : 845.4819; Found: 845.4841.

https://images.nature.com/full/nature-assets/nature/journal/v533/n7603/extref/nature17967-s1.pdf

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

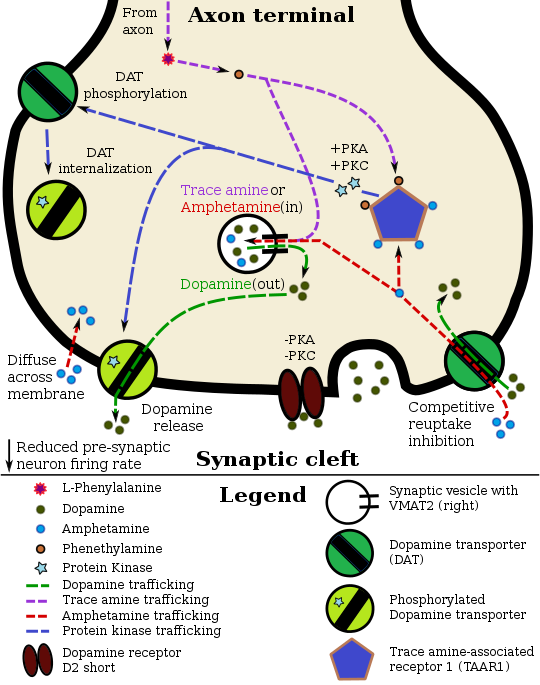

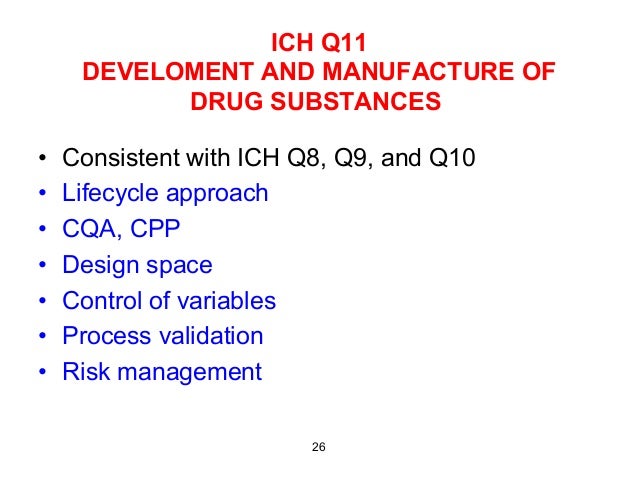

Potential causes for the formation of synthetic impurities that are present in solithromycin (1) during laboratory development are studied in the article. These impurities were monitored by HPLC, and their structures are identified on the basis of MS and NMR spectroscopy. In addition to the synthesis and characterization of these seven impurities, strategies for minimizing them to the level accepted by the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) are also described.

![Summary of macrolide antibiotic development by semisynthesis.]()

PAPER

Identification, Characterization, Synthesis, and Strategy for Minimization of Potential Impurities Observed in the Synthesis of Solithromycin

† HEC Research and Development Center, HEC Pharm Group, Dongguan 523871, P. R. China

‡ State Key Laboratory of Anti-Infective Drug Development, Sunshine Lake Pharma Co., Ltd., Dongguan 523871, P. R. China

Org. Process Res. Dev., Article ASAP

DOI: 10.1021/acs.oprd.7b00201

Macrolide antibacterial agents are characterized by a large lactone ring to which one or more deoxy sugars, usually cladinose and desosamine, are attached. The first generation macrolide, erythromycin, was soon followed by second generation macrolides clarithromycin and azithromycin. Due to widespread of bacterial resistance semi-synthetic derivatives, ketolides, were developed. These, third generation macrolides, to which, for example, belongs telithromycin, are used to treat respiratory tract infections. Currently, a fourth generation macrolide, solithromycin (also known as CEM-101 ) belonging to the fluoroketolide class is in the pre-registration stage. Solithromycin is more potent than third generation macrolides, is active against macrolide-resistant strains, is well-tolerated and exerts good PK and tissue distribution.

PATENT

https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/detail.jsf?docId=WO2017118690&recNum=1&maxRec=&office=&prevFilter=&sortOption=&queryString=&tab=PCTDescription

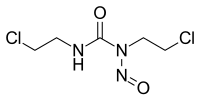

One route of synthesis of solithromycin is disclosed in WO2004/080391 A2. Said route is based on the synthetic strategy disclosed in Tetrahedron Letters, 2005, 46, 1483-1487. It is formally a 10 step linear synthesis starting from clarithromycin. Its characteristics are a late cleavage of cladinose, a hexose deoxy sugar which is in ketolides replaced with a keto group, and a 3-step building up of the side chain. Most intermediates are amorphous or cannot be purified by crystallization, hence chromatographic separations are required.

WO 2009/055557 A1 describes a process, in which the linker part of the side chain (azidobutyl) is synthesized separately thus making the synthesis more convergent. In addition, the benzoyl protection group instead of the acetyl is used to protect the 3-hydroxy group of the tetrahydropyran moiety. The linker part of the side chain is introduced using 4-azidobutanamine which is prepared through a selective Staudinger monoreduction of 1 ,4-diazidobutane.

WO 2014/145210 A1 discloses several routes of synthesis all based on the use of already fully constructed side chain building blocks, or its protected forms, which are reacted with an imidazoyl carbamate still containing the protected cladinose moiety. After the introduction of the side chain, the cladinose is cleaved and the aniline group protected for the oxidation of the hydroxy group and the fluorination. After fluorination and deprotection or unmasking of the aniline group, solithromycin is obtained.

Synthesis of crude solithromycin

A third aspect of the invention is a process for providing crude solithromycin (the compound of formula 5) through a convergent synthesis that combines both aforementioned building blocks, the macrolide building block (compound of formula 3) and the side chain building block 3-(1 -(4-aminobutyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-4-yl)aniline prepared as discussed above.

As shown in Scheme 4, first, the compound of formula 3 and 3-(1-(4-aminobutyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-4-yl)aniline are reacted in the presence of a strong base, for example, DBU, in a suitable solvent, for example, MeCN, to give the compound of formula 4. In the last step, the acetyl protecting group of the hydroxy group located on position β to the dimethylamino substituent is cleaved in methanol.

As discussed above, the fluorination is performed in the presence of acetyl group in the pyran part of the molecule and prior to the incorporation of the side chain, which allows that both exchanging the protection group in the pyran part of the molecule and masking or protecting the aniline moiety from oxidation caused under fluorinating conditions can be avoided.

![]()

Scheme 4: Representation of the specific embodiment of the present invention.

In another aspect of the present invention a process is provided for purification of crude solithromycin.

Purification of crude solithromycin

Due to its properties, solithromycin is very difficult to purify. The amorphous material obtained after various syntheses is truly a challenge for further processing.

Chromatographic separation is very difficult and of poor resolution. Due to the basic polar functional groups, the compound and its related impurities all tend to “trail” on typical normal stationary phases that are considered suitable for industrial use, such as silica and alumina. Purification by crystallization is just as difficult unless the material is already sufficiently pure. Impurities inhibit its crystallization to such an extent that solutions in alcohols can be stable even in concentrations of several-fold above the saturation levels of the pure material. Such solutions refuse to crystallize even after weeks of stirring or cooling. Seeding with crystalline solithromycin has no effect and the added seeds simply dissolve. In addition, only limited purification is achieved in most solvents. Lower primary alcohols, particularly ethanol, are most efficient for purification by crystallization when this is possible, but give low recovery and the crystallization is most sensitive toward impurities, thus still demanding prior chromatographic separation.

Clearly an alternative method of purification would be advantageous. For this reason we developed a process for purification employing an acidic salt formation, for example solithromycin oxalate salt, freebasing back to solithromycin, and crystallization from ethanol (Scheme 5).

![]()

Scheme 5: Representation of a particular embodiment of the present invention.

The formation of crystalline salts from crude solithromycin may be inhibited by impurities and is dependent on the solvent used. Only a limited number of acids gave useful precipitates from solutions of crude solithromycin. Of these, the precipitation of the oxalate salt from isopropyl acetate (‘PrOAc) or 2-methyltetrahydrofuran (MeTHF) was found to be most efficient in regard to yields, reaction times and purification ability. Precipitation of the citrate salt from MeTHF also significantly increased purity. However, impurities strongly inhibited crystal growth rates, the reaction thus required longer times compared to the oxalate salt formation. Crystallization of salts from solutions of impure solithromycin was also found possible with D-(-)-tartaric, dibenzoyl-d-tartaric, 2,4-dihydroxybenzoic, 3,5-dihydroxybenzoic, and (R)-(+)-2-pyrrolidinone-5-carboxylic acids using ethyl acetate, isopropyl acetate or MeTHF as solvents, or their mixtures with methyl f-butyl ether, but the efficiency and purification abilities were inferior to both the oxalate and the citrate salt.

Some acids, such as (R)-(-)-mandelic, L-(+)-tartaric, p-toluenesulfonic, benzoic, malonic, 4-hydroxybenzoic, (-)-malic, and (+)-camphor-10-sulfonic acid formed insoluble amorphous precipitates without improving purity. Many other acids were found unable of forming any precipitate from impure solithromycin under the conditions tested.

Example 1 : Synthesis of compound 2: (2R,3S,7R,9R, 10R, 1 1 R, 13R,Z)-10-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-3- acetoxy-4-(dimethylamino)-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-2-ethyl-9- methoxy-3,5,7,9,1 1 , 13-hexamethyl-6,12, 14-trioxooxacyclotetradec-4-en-3-yl 1 H- imidazole-1 -carboxylate

![]()

A solution of (2S,3R,4S,6R)-4-(dimethylamino)-2-(((3R,5R,6R,7R,9R,13S,14R,Z)-14-ethyl-13-hydroxy-7-methoxy-3,5,7,9,11,13-hexamethyl-2,4,10-trioxooxacyclotetradec-11-en-6-yl)oxy)-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl acetate, 1 (313 g) in dichloromethane (2.22 L) was cooled to -25 °C. DBU (115 mL) followed by CDI (125 g) were added and temperature of the reaction was raised to 0°C. The completion of the reaction was followed by HPLC. Upon the completion, the pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 6 using 10% aqueous acetic acid. Layers were separated and organic layer was washed twice with water, dried over sodium sulphate and concentrated to afford compound 2 as white foam (HPLC purity: 90 area%).

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCI3) δ 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.28 (t, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (dd, J = 1.6, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (s, 1H), 5.58 (dd, J = 10.0, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 5.22 (s, 3H), 4.61 (dd, J = 10.5, 7.6 Hz, 1H), 4.25 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 4.02 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H), 3.67 (q, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 3.42-3.37 (m, 1H), 3.04 (brs, 1H), 2.93 (quintet, J =7.7 Hz, 1H), 2.67 (s, 3H), 2.58-2.52 (m, 1H), 2.13 (s, 6H), 1.94 (s, 3H), 1.77 (s, 3H), 1.72 (d, J = 0.8 Hz, 3H), 1.64-1.53 (m, 2H), 1.25 (d, J = 6.9, 3H), 1.19 (s, 3H), 1.13 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H), 1.11 (d, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H), 1.02 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H), 0.84 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCI3) δ 204.84, 203.63, 169.64, 168.79, 145.85, 138.48, 137.94, 136.95, 130.75, 117.04, 101.78, 84.45, 80.77, 78.44, 76.89, 71.38, 69.02, 63.37, 50.91, 50.13, 47.31, 40.48, 40.48, 40.16, 38.81, 30.12, 22.53, 21.27, 20.84, 20.56, 20.06, 18.81, 14.98, 13.91, 13.14, 10.37.

Example 2: Synthesis of compound 3: (2R,3S,7R,9R, 10R, 11 R, 13S,Z)-10-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-3- acetoxy-4-(dimethylamino)-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-2-ethyl-13- fluoro-9-methoxy-3,5,7,9, 11,13-hexamethyl-6, 12, 14-trioxooxacyclotetradec-4-en- 3-yl 1H-imidazole-1-carboxylate

![]()

A solution of (2R,3S,7R,9R,10R,11 R,13R,Z)-10-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-3-acetoxy-4-(dimethylamino)-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-2-ethyl-9-methoxy-3,5,7,9,11,13-hexamethyl-6,12,14-trioxooxacyclotetradec-4-en-3-yl 1H-imidazole-1-carboxylate, 2 in THF (9 L) was cooled to 0 °C. DBU (115 mL) followed by NFSI (211 g) were added and reaction mixture was stirred at 0°C

until completion (followed by HPLC). The reaction mixture was quenched with cold, diluted NaHC03 (3 L). DCM (2.5 L) was added and layers were separated. Aqueous layer was washed with additional DCM (1.5 L). Combined organic layers were washed with brine (2 L), dried over sodium sulphate, filtrated and concentrated. Crude material was suspended in /‘PrOAc (2.5 L). Undissolved material was filtered-off and filtrate was concentrated in vacuo to afford compound 3 as pale yellow foam (475 g, HPLC purity: 85 area%).

19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCI3) δ -163.1 1.

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCI3)5 204.81 , 202.27, 169.59, 165.51 (d, J = 22.9 Hz), 145.64, 138.02, 137.78, 136.85, 130.69, 1 16.95, 101 .57, 97.86 (d, J = 204.5 Hz), 84.23, 80.23, 78.95, 77.97, 71.24, 68.92, 63.1 1 , 49.05, 40.48, 40.48, 40.40, 40.08, 30.22, 24.18 (d, J = 16.8 Hz), 22.62, 21.64, 21 .18, 20.76, 19.97, 19.39, 14.37, 13.13, 10.32.

Synthesis of compound 3. (2R,3S,7R,9R, 10R, 1 1 R, 13S,Z)-10-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-3- acetoxy-4-(dimethylamino)-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-2-ethyl-13- fluoro-9-methoxy-3,5,7,9, 1 1 , 13-hexamethyl-6, 12, 14-trioxooxacyclotetradec-4-en- 3-yl 1 H-imidazole-1 -carboxylate

![]()

A solution of (2S,3R,4S,6R)-4-(dimethylamino)-2-(((3R,5R,6R,7R,9R,13S,14R,Z)-14-ethyl-13-hydroxy-7-methoxy-3,5,7,9,1 1 , 13-hexamethyl-2,4, 10-trioxooxacyclotetradec-1 1-en-6-yl)oxy)-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl acetate, 1 (2.45 g) in THF (17 mL) was cooled to 0 °C. DBU (0.9 mL) followed by CDI (0.97 g) were added. The completion of the reaction was followed by HPLC. Upon the completion, reaction was diluted by addition of THF (34 mL). Temperature of the reaction was lowered to -10 °C. DBU (0.72 mL) was added followed by solution of NFSI (1.51 g) in THF (14 mL). Upon completion of the reaction, mixture was diluted with the addition of water/ZPrOAc (1 :4) mixture and layers were separated. Organic phase was washed with water (3 x 25 mL), dried over Na2S04, filtered and concentrated to afford compound 3 as a white foam (3.1 g, HPLC purity: 70 area%).

Example 4: Synthesis of 3-(1 -(4-aminobutyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-4-yl)aniline

K2

![]()

1 moi% CuS04(aq)

2-(4-Chlorobutyl)isoindoline-1 ,3-dione. A mixture of phthalimide potassium salt (1 134 g, 6.00 mol), potassium carbonate (209 g, 1.50 mol), 1 ,4-dichlorobutane (1555 g, 12.00 mol), and potassium iodide (51 g, 0.30 mol, 5 mol%) in 2-butanone (4.80 L) was stirred 3 days at reflux conditions. The reaction mixture cooled to 40 °C was filtered and the insoluble materials washed with 2-butanone (1.00 L). The filtrate was evaporated at 80 °C under reduced pressure. 2-Propanol (1.00 L) was added to the residue and the solvent removed under reduced pressure. The residue was then crystallized from 2-propanol (4.30 L) at 25 °C. The product was isolated by filtration and washed with 2-propanol (1.00 L). After drying at 40 °C and approximately 50 mbar, there was obtained a white powder (1 1 1 1 g): 95% assay by quantitative 1H NMR; MS (ESI) m/z = 238 [MH]+.

2-(4-(4-(3-Aminophenyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-l -yl)butyl)isoindoline-1 ,3-dione. To a solution of 2-(4-chlorobutyl)isoindoline-1 ,3-dione (950 g, 4.00 mol) in DMSO (2.80 L) was added sodium azide (305 g) and the mixture stirred 4 h at 70 °C. The reaction temperature was reduced to 25 °C and there was added in this order water (0.80 L), ascorbic acid (43 g, 0.24 mol, 6 mol%), 0.5M CuS04(aq) (160 ml_, 2 mol%) and m-aminophenylacetylene (493 g, 4.00 mol). The resulting mixture was stirred 18 h at 40 °C, forming a thick yellow slurry, which was then cooled to 0 °C and slowly diluted with water (2.40 L). The product was isolated by filtration, washing the filter cake with water (3 χ 2.00 L) and a 1 : 1 (vol.) mixture of methanol and water (2.00 L). After drying at 50 °C and approximately 50 mbar the product was obtained as a yellow powder (1405 g): 85% assay by quantitative 1H NMR; MS (ESI) m/z = 362 [MH]+.

3-(1-(4-Aminobutyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl)aniline. To a stirred suspension of 2-(4-(4-(3-Aminophenyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-1 -yl)butyl)isoindoline-1 ,3-dione (659 g, 1 .55 mol) in 1 -butanol (3.26 L) was added hydrazine hydrate (50-60%, 174 ml_). After stirring for 18 h at 60 °C there was added toluene (0.72 L) and 1 M NaOH(aq) (5.00 L). After stirring for 20 min at 60 °C, the aqueous phase was removed and the organic phase washed at this same temperature with 1 M NaOH(aq) (1 .00 L), saturated NaCI(aq) (2 χ 2.00 L), and concentrated under reduced pressure to 2/3 of the initial quantity, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate (300 g) in the presence of Fluorisil (30 g), filtered and evaporated under reduced pressure at 70 °C. The residual 1 -butanol is removed azotropically by adding toluene and evaporation under reduced pressure (2 χ 0.50 L). The residue was dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (0.50 L). To this solution kept stirring at 25 °C was slowly added methyl t-butyl ether (0.50 L) at which point the mixture was seeded. Additional methyl t-butyl ether (0.50 L) was slowly added and the product isolated by filtration, washed with methyl t-butyl ether (0.50 L), and dried at 35 °C and approximately 50 mbar to give an amber colored powder (321 g): mp = 70-73 °C (DSC);

1 H NMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) 1 .30 (m, 2H), 1 .86 (m, 2H), 2.3-2.1 (bs, 2H), 2.53 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 2H), 4.35 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 5.17 (bs, 2H), 6.51 (ddd, J = 8.0, 2.3, 1 .0 Hz, 1 H), 6.92 (m, 1 H), 7.05 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1 H), 7.09 (t, J = 1 .9 Hz, 1 H), 8.39 (s, 1 H); 98% assay by quantitative 1 H NMR; MS (ESI) m/z = 232 [MH]+; I R (NaCI) 694, 789, 863, 1220, 1315, 1467, 1487, 1590, 2935 cm“1.

Example 5: Synthesis of compound 4: (2S,3R,4S,6R)-2-(((3aS,4R,7S,9R, 10R, 1 1 R, 13R,

15R)-1 -(4-(4-(3-aminophenyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-1 -yl)butyl)-4-ethyl-7-fluoro-1 1 – methoxy-3a,7,9, 1 1 , 13, 15-hexamethyl-2,6,8, 14-tetraoxotetradecahydro-1 H- [1 ]oxacyclo-tetradecino[4,3-d]oxazol-10-yl)oxy)-4-(dimethylamino)-6-methyltetra- hydro-2H-pyran-3-yl acetate

![]()

A solution of (2R,3S,7R,9R,10R, 1 1 R, 13S,Z)-10-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-3-acetoxy-4-(dimethylamino)-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-2-ethyl-13-fluoro-9-methoxy-3,5,7,9, 1 1 , 13-hexamethyl-6, 12,14-trioxooxacyclotetradec-4-en-3-yl 1 H-imidazole-1-carboxylate (425 g) in acetonitrile (3.1 L) was cooled to 0 °C. 4-(1-(4-aminobutyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-4-yl)aniline, 3 (213 g) followed by DBU (83 ml.) were added. The mixture was stirred at 0° C until completion of the reaction (followed by HPLC). Mixture of DCM and water was added (4 L, 1 :1 ) and the pH was adjusted to 6 with 10% aqueous acetic acid. Layers were separated and organic layer was washed with water (2 x 2 L), dried over sodium sulphate and concentrated. The crude material was suspended in EtOAc (2.5 L). Undissolved material was filtered off and filtrate was concentrated in vacuo to afford compound 4 as yellow foam (470 g, HPLC purity: 75 area%).

19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCI3) δ -164.17 (q, J = 21.3 Hz).

13C NMR (125MHz, CDCI3) δ 216.67, 202.47 (d, J = 28.2 Hz), 169.88, 166.44 (d, J = 23.1 Hz), 157.28, 147.92, 147.00, 131 .81 , 129.73, 1 19.80, 1 16.16, 1 14.81 , 1 12.42, 101.90, 98.02 (d, J =205.9 Hz), 82.18, 79.74, 78.72, 71 .68, 69.33, 63.33, 61 .13, 49.80, 49.31 , 44.61 , 42.85, 40.71 , 39.37, 39.28, 31.97, 30.53, 29.1 1 , 27.69, 25.24 (d, J = 22.2 Hz), 24.36, 22.78, 22.24, 21.49, 21.04, 19.80, 18.04, 14.78, 14.70,14.21 , 13.83, 10.57.

Example 11 : Purification of crude solithromycin (compound 5) via oxalate (2)

To isopropyl acetate (5.77 L) crude solithromycin (192 g, 72 area%) was added, afterwards the mixture was stirred at reflux and filtered to remove any insoluble material. The filtrate was then stirred at 55 °C and oxalic acid (14.91 g, 164 mmol) was added in one batch. The suspension was cooled to 20 °C in the course of 1 h, stirred for additional 1 h and the product was isolated by filtration, washed with isopropyl acetate (0.5 L), and dried at 40 °C under reduced pressure to give the oxalate salt (106 g): 87.81 area% by HPLC (UV at 228 nm). The evaporation of the filtrate gave a resinous material containing solithromycin that can be recovered by reprocessing (88 g, 61.13 area%).

The above oxalate salt (106 g) was dissolved in water (2.40 L) and washed with MeTHF (2 χ 1.00 L) and ethyl acetate (0.50 L). Aqueous ammonia (25%; 37 mL) was then added to the filtrate while stirring at 25 °C. The precipitated product was extracted with ethyl acetate two times (3.00 L and 0.50 L). The combined extracts were washed with water (0.50 L), dried over Na2S04 and evaporated under reduced pressure. To the residue ethanol (2 χ 0.4 L) was added and again evaporated to affect the solvent exchange. The residue was then dissolved in ethanol (300 mL). After stirring for 24 h at 25 °C, the crystallized product was isolated by filtration and drying at 40 °C under reduced pressure to give solithromycin as an off-white crystalline solid (42 g): 98.61 area% by HPLC (UV at 228 nm).

The filtrate was evaporated under reduced pressure to give a yellowish foam (29 g: 68.65 area% by HPLC (UV at 228 nm) that was used for reprocessing.

Example 7: Purification of compound 5 (solithromycin): (3aS,4R,7S,9R, 10R, 1 1 R, 13R, 15R)-1 – (4-(4-(3-aminophenyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-1 -yl)butyl)-10-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-4- (dimethylamino)-3-hydroxy-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-4-ethyl-7- fluoro-1 1 -methoxy-3a,7,9, 1 1 , 13, 15-hexamethyloctahydro-1 H- [1 ]oxacyclotetradecino[4,3-d]oxazole-2,6,8, 14(7H, 9H)-tetraone

Crude solithromycin 5 (106 g, HPLC purity: 71 %) was suspended in /‘PrOAc (3 L) and heated to reflux, then filtered to remove undissolved material. Oxalic acid (8 g) was added to a filtrate at 60°C. Mixture was slowly cooled to RT and left stirring for additional 1 h. Precipitate was filtered off and dried in vacuo. Oxalate salt was suspended in water (1 .3 L) (if needed mixture was first filtered through Celite) then 25% aqueous ammonia (21 mL) was added and mixture was stirred additional 15 minutes. Precipitate was filtered off, rinsing with water. Wet solithromycin was dissolved it EtOAc (1 .8 L)/water (800 mL) solution. Layers were separated and organic phase was washed with water (2 x 250 mL), dried over Na2S04 and filtered. EtOAc was removed in vacuo to afford yellow foam.

Yellow foam was dissolved in EtOH (230 mL) and left stirring at RT until white precipitate fell out. White precipitate was dried in vacuo at room temperature to afford clean material (HPLC purity 97 area%).

19F NMR (470 MHz, CDCI3) δ -164.25 (q, J = 21 .3 Hz).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCI3) δ 216.64, 202.90 (d, J = 28.2 Hz), 166.53 (d, J = 23.2 Hz), 157.27, 147.88, 146.99, 131 .76, 129.70, 1 19.79, 1 16.1 1 , 1 14.79, 1 12.38, 104.31 , 97.84 (d, J = 206.1 Hz), 82.19, 80.77, 78.65, 78.58, 70.41 , 69.71 , 65.84, 61 .09, 49.77, 49.28, 44.64, 42.84, 40.92, 40.30, 39.61 , 39.26, 28.17, 27.66, 25.29 (d, J = 22.5 Hz), 24.32, 22.20, 21 .23, 19.82, 17.96, 15.12, 14.77, 13.83, 10.54.

Example 6: Synthesis of compound 5 (solithromycin): (3aS,4R,7S,9R, 10R, 1 1 R, 13R,15R)-1- (4-(4-(3-aminophenyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-1-yl)butyl)-10-(((2S,3R,4S,6R)-4- (dimethylamino)-3-hydroxy-6-methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)oxy)-4-ethyl-7- fluoro-1 1 -methoxy-3a,7,9, 1 1 , 13, 15-hexamethyloctahydro-1 H- [1]oxacyclotetradecino[4,3-d]oxazole-2,6,8, 14(7H,9H)-tetraone

![]()

A solution of (2S,3R,4S,6R)-2-(((3aS,4R,7S,9R, 10R, 1 1 R, 13R, 15R)-1 -(4-(4-(3-aminophenyl)-1 H-1 ,2,3-triazol-1 -yl)butyl)-4-ethyl-7-fluoro-1 1 -methoxy-3a,7,9, 1 1 , 13,15-hexamethyl-2,6,8, 14-tetraoxotetradecahydro-1 H-[1 ]oxacyclotetradecino[4,3-d]oxazol-10-yl)oxy)-4-(dimethylamino)-6- methyltetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-yl acetate, 4 (470 g) in methanol (4.7 L) was stirred at room temperature and completion of the reaction was followed by HPLC. Upon completion, the reaction mixture was concentrated to afford crude solithromycin 5 as orange foam (402 g, HPLC purity: 73 area%).

References

- Jump up^ Reinert RR (June 2004). “Clinical efficacy of ketolides in the treatment of respiratory tract infections”. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 53 (6): 918–27. PMID 15117934. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh169.

- Jump up^ http://www.cempra.com/research/antibacterials/

- Jump up^ Woolsey LN; Castaneira M; Jones RN. (May 2010). “CEM-101 activity against Gram-positive organisms”. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (5): 2182–2187. PMC 2863667

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 20176910. doi:10.1128/AAC.01662-09.

. PMID 20176910. doi:10.1128/AAC.01662-09.

- Jump up^ Farrell DJ; Sader HS; Castanheira M; Biedenbach DJ; Rhomberg PR; Jones RN. (June 2010). “Antimicrobial characterization of CEM-101 activity against respiratory tract pathogens including multidrug-resistant pneumococcal serogroup 19A isolates”. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 35 (6): 537–543. PMID 20211548. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.01.026.

- Jump up^ McGhee P; Clark C; Kosowska-Shick K; Nagai K; Dewasse B; Beachel L; Appelbaum PC. (January 2010). “In Vitro Activity of Solithromycin against Streptococcus pneumoniae andStreptococcus pyogenes with Defined Macrolide Resistance Mechanisms”. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (1): 230–238. PMC 2798494

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 19884376. doi:10.1128/AAC.01123-09.

. PMID 19884376. doi:10.1128/AAC.01123-09.

- Jump up^ Putnam, Shannon D.; Castanheira, Mariana; Moet, Gary J.; Farrell, David J.; Jones, Ronald N. (2010). “CEM-101, a novel fluoroketolide: antimicrobial activity against a diverse collection of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria”. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 66 (4): 393–401. PMID 20022192. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.10.013.

- Jump up^ Putnam, Shannon D.; Sader, Helio S.; Farrell, David J.; Biedenbach, Douglas J.; Castanheira, Mariana (2011). “Antimicrobial characterisation of solithromycin (CEM-101), a novel fluoroketolide: activity against staphylococci and enterococci”. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. 37 (1): 39–45. PMID 21075602. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.08.021.

- Jump up^ “Intravenous (IV) Administration of Cempra Pharmaceutical’s Solithromycin (CEM-101) Demonstrates Excellent Systemic Tolerability in a Phase 1 Clinical Trial”. 7 May 2011.

- Jump up^ “Cempra antibiotic compound as effective, safer than levofloxacin”. 15 Sep 2011.

- Jump up^ http://investor.cempra.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=889300. 4 Jan 2015

- Jump up^ http://investor.cempra.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=920866. 7 July 2015

- Jump up^ http://investor.cempra.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=936994

- Jump up^ http://investor.cempra.com/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=978096

- Jump up^ Llano-Sotelo B, Dunkle J, Klepacki D, Zhang W, Fernandes P, Cate JH, Mankin AS (2010). “Binding and Action of CEM-101, a New Fluoroketolide Antibiotic That Inhibits Protein Synthesis”. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (12): 4961–4970. PMC 2981243

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 20855725. doi:10.1128/AAC.00860-10.

. PMID 20855725. doi:10.1128/AAC.00860-10.

- Jump up^ Bertrand D, Bertrand S, Neveu E, Fernandes P (2010). “Molecular characterization of off-target activities of telithromycin: a potential role for nicotinic acetylcholine receptors”. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (12): 599–5402. PMC 2981250

![Freely accessible Freely accessible]() . PMID 20855733. doi:10.1128/AAC.00840-10.

. PMID 20855733. doi:10.1128/AAC.00840-10.

Further reading

/////////////Solithromycin, солитромицин , سوليثروميسين , 索利霉素 , CEM-101, OP-1068, UNII:9U1ETH79CK

|

[H][C@]12N(CCCCN3C=C(N=N3)C3=CC(N)=CC=C3)C(=O)O[C@]1(C)[C@@]([H])(CC)OC(=O)[C@@](C)(F)C(=O)[C@]([H])(C)[C@@]([H])(O[C@]1([H])O[C@]([H])(C)C[C@]([H])(N(C)C)[C@@]1([H])O)[C@@](C)(C[C@@]([H])(C)C(=O)[C@]2([H])C)OC

|

Filed under:

Uncategorized Tagged:

CEM-101,

索利霉素,

солитромицин,

OP-1068,

solithromycin,

UNII:9U1ETH79CK,

سوليثروميسين ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(Ref. 0001)Optical rotation

(Ref. 0001)Optical rotation

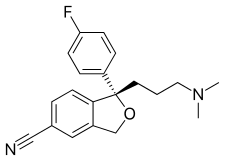

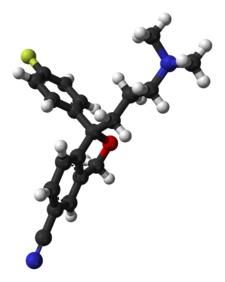

The Grignard condensation of 5-cyanophthalide (I) with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (II) in THF gives 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxy-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile bromomagnesium salt (III), which slowly rearranges to the benzophenone (IV). A new Grignard condensation of (IV) with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (V) in THF affords the expected bis(magnesium) salt (VI), which is hydrolyzed with acetic acid to provide the diol (VII) as a racemic mixture. Selective esterification of the primary alcohol of (VII) with (+)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride (VIII) gives the monoester (IX) as a mixture of diastereomers. This mixture is separated by HPLC and the desired diastereomer (X) is treated with potassium tert-butoxide in toluene.

The Grignard condensation of 5-cyanophthalide (I) with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (II) in THF gives 1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-hydroxy-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carbonitrile bromomagnesium salt (III), which slowly rearranges to the benzophenone (IV). A new Grignard condensation of (IV) with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (V) in THF affords the expected bis(magnesium) salt (VI), which is hydrolyzed with acetic acid to provide the diol (VII) as a racemic mixture. Selective esterification of the primary alcohol of (VII) with (+)-3,3,3-trifluoro-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride (VIII) gives the monoester (IX) as a mixture of diastereomers. This mixture is separated by HPLC and the desired diastereomer (X) is treated with potassium tert-butoxide in toluene. A new method for the preparation of citalopram has been developed: The chlorination of 1-oxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid (I) with refluxing SOCl2 gives the acyl chloride (II), which is condensed with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (III) in THF yielding the corresponding amide (IV). The cyclization of (IV) by means of SOCl2 affords the oxazoline (V), which is treated with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (VI) in THF giving the benzophenone (VII). This compound (VII), without isolation, is treated with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (VIII) in the same solvent, providing the cabinol (IX), which is cyclized by means of methanesulfonyl chloride and Et3N in CH2Cl2 yielding the isobenzofuran (X). Finally, this compound is treated with POCl3 in refluxing pyridine to generate the 5-cyano substituent of citalopram.

A new method for the preparation of citalopram has been developed: The chlorination of 1-oxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid (I) with refluxing SOCl2 gives the acyl chloride (II), which is condensed with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (III) in THF yielding the corresponding amide (IV). The cyclization of (IV) by means of SOCl2 affords the oxazoline (V), which is treated with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (VI) in THF giving the benzophenone (VII). This compound (VII), without isolation, is treated with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (VIII) in the same solvent, providing the cabinol (IX), which is cyclized by means of methanesulfonyl chloride and Et3N in CH2Cl2 yielding the isobenzofuran (X). Finally, this compound is treated with POCl3 in refluxing pyridine to generate the 5-cyano substituent of citalopram. The chlorination of 1-oxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid (XII) with refluxing SOCl2 gives the acyl chloride (XIII), which is condensed with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (XIV) in THF to yield the corresponding amide (XV). The cyclization of (XV) by means of SOCl2 affords the oxazoline (XVI), which is treated with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (XVII) in THF to give the benzophenone (XVIII). This compound (XVIII), without isolation, is treated with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (XIX) in the same solvent to provide the carbinol (XX), which is submitted to optical resolution with (+)- or (-)-tartaric acid, or (+)- or (-)-camphor-10-sulfonic acid (CSA) to give the desired (S)-enantiomer (XXI). Cyclization of (XXI) by means of methanesulfonyl chloride and TEA in dichloromethane yields the chiral isobenzofuran (XXII), which is finally treated with POCl3 in refluxing pyridine.

The chlorination of 1-oxo-1,3-dihydroisobenzofuran-5-carboxylic acid (XII) with refluxing SOCl2 gives the acyl chloride (XIII), which is condensed with 2-amino-2-methyl-1-propanol (XIV) in THF to yield the corresponding amide (XV). The cyclization of (XV) by means of SOCl2 affords the oxazoline (XVI), which is treated with 4-fluorophenylmagnesium bromide (XVII) in THF to give the benzophenone (XVIII). This compound (XVIII), without isolation, is treated with 3-(dimethylamino)propylmagnesium chloride (XIX) in the same solvent to provide the carbinol (XX), which is submitted to optical resolution with (+)- or (-)-tartaric acid, or (+)- or (-)-camphor-10-sulfonic acid (CSA) to give the desired (S)-enantiomer (XXI). Cyclization of (XXI) by means of methanesulfonyl chloride and TEA in dichloromethane yields the chiral isobenzofuran (XXII), which is finally treated with POCl3 in refluxing pyridine.

The esterification of racemic 1-[4-bromo-2-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl]-4-(dimethylamino)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-butanol (I) with (S)-2-(6-methoxynaphth-2-yl)propionyl chloride (II) by means of TEA and DMAP in THF gives the corresponding ester (III) as a diastereomeric mixture that is separated by chiral chromatography over Daicel AD, the desired diastereomer (IV) is easily isolated. Finally, this ester is hydrolyzed and simultaneously cyclized by means of NaH in DMF to provide the target intermediate (V). Other acyl chlorides such as (S)-2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propionyl chloride, (S)-O-acetylmandeloyl chloride, (S)-benzyloxycarbonylprolyl chloride, (S)-2-phenylbutyryl chloride, (S)-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride or (S)-N-acetylalanine can also be used in the preceding sequence.

The esterification of racemic 1-[4-bromo-2-(hydroxymethyl)phenyl]-4-(dimethylamino)-1-(4-fluorophenyl)-1-butanol (I) with (S)-2-(6-methoxynaphth-2-yl)propionyl chloride (II) by means of TEA and DMAP in THF gives the corresponding ester (III) as a diastereomeric mixture that is separated by chiral chromatography over Daicel AD, the desired diastereomer (IV) is easily isolated. Finally, this ester is hydrolyzed and simultaneously cyclized by means of NaH in DMF to provide the target intermediate (V). Other acyl chlorides such as (S)-2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propionyl chloride, (S)-O-acetylmandeloyl chloride, (S)-benzyloxycarbonylprolyl chloride, (S)-2-phenylbutyryl chloride, (S)-2-methoxy-2-phenylacetyl chloride or (S)-N-acetylalanine can also be used in the preceding sequence.

The thiourea catalyst L7 bearing 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl) benzene and dimethylamino groups has been revealed to be efficient for the asymmetric Michael reaction of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds to nitroolefins (Scheme 8). This methodology has been applied for the total synthesis of (R)-(−)-baclofen. Reaction of 4-chloronitrostyrene and 1,3-dicarbonyl compound generates quaternary carbon center with 94% ee. Reduction of the nitro gruop to amine and subsequent cyclization, esterification and ring opening provides ( R )-(−)-baclofen in 38% yield.

The thiourea catalyst L7 bearing 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl) benzene and dimethylamino groups has been revealed to be efficient for the asymmetric Michael reaction of 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds to nitroolefins (Scheme 8). This methodology has been applied for the total synthesis of (R)-(−)-baclofen. Reaction of 4-chloronitrostyrene and 1,3-dicarbonyl compound generates quaternary carbon center with 94% ee. Reduction of the nitro gruop to amine and subsequent cyclization, esterification and ring opening provides ( R )-(−)-baclofen in 38% yield.